The Announcement and Its Frame

Penguin Random House announced the forthcoming publication of Unbroken: In Pursuit of Freedom for Palestine by Marwan Barghouti in early 2026, presenting it as a major political and literary event. The announcement appeared through Penguin’s catalog channels and was picked up by mainstream cultural and book-industry media, including rights reporting in The Bookseller and broader publishing trade visibility via BookBrunch, as well as general press coverage in outlets such as The Guardian and Arab News. The publisher framed the book as a rare opportunity for global readers to encounter Barghouti’s political thought directly, rather than through the mediation of journalists, analysts, or diplomatic discourse.

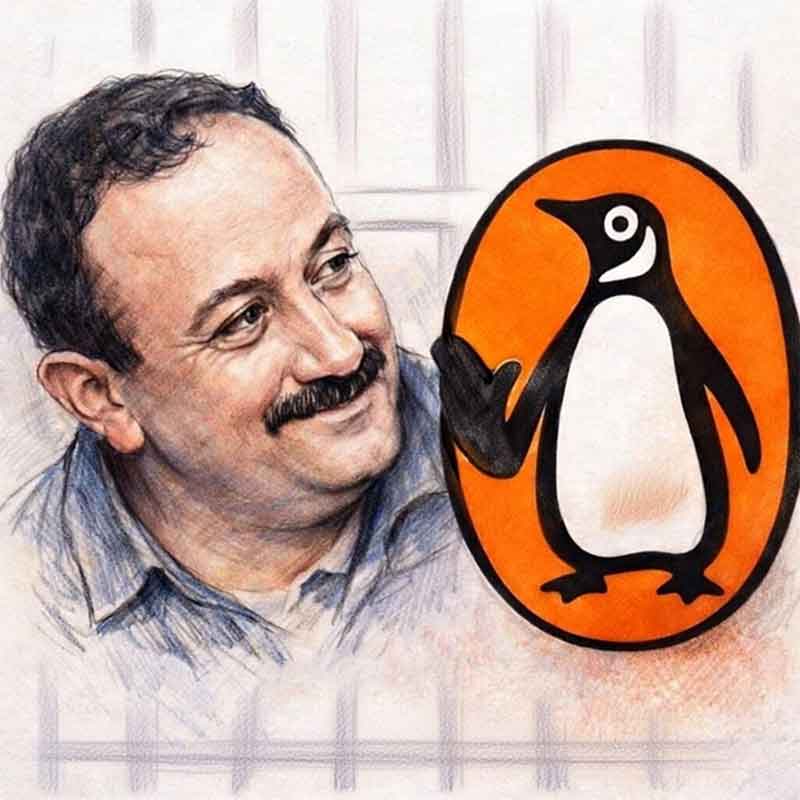

Marwan Barghouti stands as one of the most influential political leaders to emerge from the Palestinian national movement since the Oslo Accords, often compared — by admirers and media alike — to Nelson Mandela. He built political credibility through organizing under occupation, confronting Israeli military rule, and maintaining independence from donor-driven and security-coordinated governance. Israel imprisoned him in 2002 following a trial widely criticized as politically motivated, ostensibly to neutralize a leader who could mobilize collective action beyond the narrow confines of diplomatic processes, Israel’s security imperatives, and the PA’s managed autonomy.

What we know so far underscores the unusual conditions of the book’s production. Unbroken assembles texts written under the Israeli prison system run by the Israel Prison Service (IPS) — a censorship-and-surveillance apparatus that restricts paper and writing materials, screens and withholds correspondence, and punishes prisoners for “unauthorized” communication. Barghouti’s words moved out through the narrow channels the prison cannot seal: tightly monitored lawyer visits, family contact when permitted, and trusted intermediaries who carried fragments across a system designed to suppress prisoner resistance and isolate leaders from their communities, as documented by human rights organizations like Addameer.

The book enters a global lineage of prison writing as resistance, including works from Antonio Gramsci (Italy), Nelson Mandela (South Africa), Martin Luther King Jr. (US), Malcolm X (The Autobiography of Malcolm X), Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (Soviet Union), Liu Xiaobo (China), Václav Havel (Czechoslovakia), Jacobo Timerman (Argentina), Reinaldo Arenas (Before Night Falls, Cuba), and Indigenous political prisoners such as Leonard Peltier (Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sun Dance) in the United States.

Penguin’s early framing presents the book as an “intimate portrait” of Barghouti’s life and struggle, compiling “private letters,” “personal writings,” and “rare photographs” to offer readers “his story, in his own words. Unsilenced, unbroken.” This emphasis on personal endurance subtly repositions the text as a collection of reflections produced under incarceration. The publisher invites readers to approach Barghouti primarily as a moral witness to suffering rather than as an active political leader whose analysis targets structures of domination. While this genre placement signals seriousness, courage, and endurance — values that Western literary institutions readily recognize — it subtly repositions Palestinian political thought within a culture of testimony that can be admired but not necessarily acted upon.

In other words, Penguin is containing Barghouti’s legacy: prison literature circulates most comfortably in liberal publics when it reads as ethical documentation of crueltyrather than as a call to confront the political order that produces that cruelty.

Genre as Containment: Prison Literature vs. Political Intervention

Mainstream media coverage following the announcement has largely echoed this framing. Headlines have emphasized the drama of authorship under imprisonment, the “voice from a cell,” and the rarity of access to Barghouti’s inner life. Pre-publication reporting and cultural coverage have leaned on familiar tropes — resilience, endurance, reconciliation, the promise of dialogue — while bracketing the book’s substantive political claims within neutralizing descriptors such as “controversial,” “polarizing,” or “complex.” This treats the book as an object of moral interest rather than a political intervention with real stakes for ongoing policy, military support, and diplomatic cover.

The genre cue provided by Penguin thus travels intact into mainstream coverage, obscuring the conditions that make Palestinian suffering routine.

Supportive networks — Palestinian communities, solidarity movements, decolonial scholars, and younger readers already engaged by events in Gaza — have greeted the announcement as a long-overdue breach in the wall of narrative exclusion. This reception builds on late-2025 campaigns that secured endorsements from over 200 cultural figures — including Margaret Atwood, Benedict Cumberbatch, Annie Ernaux, Ian McKellen, Tilda Swinton, and others — who signed open letters demanding Barghouti’s release and framed his imprisonment as a denial of basic rights. They have framed the book as an act of political rupture: a Palestinian leader speaking directly into global circuits that usually filter Palestinian speech through NGOs, humanitarian intermediaries, or security discourse. Accounts such as @FreeMarwanNow have celebrated Unbrokenas a powerful, unsilenced portrait of Barghouti’s life and struggle, highlighting its collection of private letters, correspondence, interviews, statements, and rare photographs as evidence of his enduring voice despite decades of imprisonment.

Oppositional networks, by contrast, are likely to mobilize around familiar delegitimization frames: questioning the publisher’s responsibility, invoking security rhetoric, and rehearsing the recurring accusation that publishing Palestinian political writing “normalizes extremism” or “legitimizes terrorism.” Historically, such responses have rarely engaged the substantive content of the work in question; instead, they have targeted the very fact of publication itself.

Any initial oppositional reaction to Penguin’s announcement would likely take the form of coordinated denunciations of the publisher — potential calls to boycott, demands that the book be withdrawn, warnings that Penguin is acting irresponsibly, and familiar claims that publishing Barghouti’s writings legitimizes terrorism.

These kinds of reactions typically move through an organized transatlantic networkof advocacy groups, policy shops, and media actors that activate whenever Palestinian political leadership enters mainstream Western cultural space. They link Israeli state–aligned advocacy groups with US and UK lobbying organizations, think tanks, and media commentators. In practice this means Israeli-linked outfits such as NGO Monitor often work in tandem with AIPAC-aligned advocacy networks and the ADL in the United States, UK Lawyers for Israel and the Campaign Against Antisemitism in Britain, and policy shops such as the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (Washington) and the Henry Jackson Society (London). They circulate shared talking points through briefings, op-eds, donor networks, campus campaigns, and rapid-response media interventions. They reproduce Israeli and US security framings of figures like Barghouti and Ahmad Sa‘adat as “terrorists” rather than political leaders rooted in a mass anti-colonial movement.

The Predicted Reception: Sympathy, Solidarity, and Backlash

The result is a split reception that mirrors the politics Penguin’s framing has set in motion. In liberal cultural space, Unbroken enters as prison literature — moving, courageous, safely human. In politicized publics, it circulates (or is poised to circulate) as a live intervention — dangerous precisely because it refuses to confine Palestinian thought to the archive of suffering. How far Penguin allows the book to travel toward the latter representation — through marketing copy, jacket framing, endorsements, and platforming choices — will determine whether Unbroken functions as moral literature that comforts readers or as dissident writing that unsettles the political order that made the prison necessary.

The Stakes: What Makes Writing “Dissident”

By dissident writing, I mean political texts produced under repression that name systems of control — occupation, incarceration, and racialized rule — for what they are; speak as part of the struggle itself, not as its managers or translators; and break through censorship and media gatekeeping that normally decide which political voices get heard. By showing how Israel’s legality masks coercion, how “security” rationalizes dispossession, and how domination becomes normalized, Barghouti’s writing potentially carries the power to unsettle a settler-colonial apartheid order.

That is a high bar. Writing under repression does not automatically become dissident writing in this sense, and we cannot assume in advance that Unbroken will meet it — especially when the publisher frames the book primarily as documentary testimony of suffering and survival, a form liberal institutions know how to absorb without altering how they govern. The question is not whether the book will move readers, but whether it will confront the system that produces the prison.

While institutional framing exerts powerful gravitational pull, it is not deterministic. The history of politically charged literature shows that readers, study groups, solidarity networks, and educators routinely perform acts of reclamation and re-politicization. A text marketed as “human interest” can be taught as a manual of resistance; excerpts labeled “personal testimony” can be mobilized as explicit indictments of policy. The ultimate text is not just the object Penguin produces, but the social text created through its use in movement spaces, on social media, and in political education. The gap between the publisher’s framing and the dissident content creates a zone of contestationwhere the book’s political meaning will be fought over, not simply received.

The Crucial Mediators: Editors, Institutions, and Historical Canons

In Barghouti’s case, editorial mediation will shape this outcome more than usual. Because access to him is severely restricted, editors and translators necessarily assemble, sequence, contextualize, and frame fragments that reached the outside world through constrained channels. That work is never neutral. It can sharpen a political argument — or soften it. It can foreground structures of domination — or repackage themas personal reflection and moral witness. The announcement framing already signals the kind of careful mediation Penguin believes is required for the book to circulate within Western cultural space.

This is not an indictment of editing per se. Editors have always shaped the political force of texts. Maxwell Perkins reorganized and cut American modernist fiction into legible form; Ezra Pound’s heavy hand on The Waste Land altered not only a poem but the direction of modernist aesthetics. More politically, editors at major Western houses have long mediated dissident and anti-colonial writing into formats that could pass through institutional filters. Editorial labor can enable dissidence to travel — but it can also discipline it.

The political question facing Unbroken is whether Penguin’s editorial and marketing apparatus will allow Barghouti’s writing to function as dissident analysis — naming structures, aligning with collective struggle, and cutting through filters that police Palestinian speech — or whether it will translate his politics into a safely human, morally moving document of suffering that confirms liberal sympathy while leaving the governing order intact. The answer will not lie in the fact of publication alone, but in how the text is assembled, framed, and made legible to power.

We can see the stakes of institutional mediation by contrast in the case of Georges Ibrahim Abdallah, whose political letters and statements circulated largely through movement media. Because they remained confined to activist circuits, Western cultural institutions could sidestep them without having to absorb or neutralize them. Barghouti’s case enters a different ground. Penguin’s platform extends the reach of his words across mainstream cultural space, and that expansion brings intensified pressure to translate dissident analysis into testimony and political indictment into “context.”What will matter is how much of Barghouti’s political force survives that passage through institutional gatekeeping.

The contrast with Czech and Eastern European dissidents sharpens the stakes. During the Cold War, figures such as Václav Havel, Milan Kundera, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsynentered Western literary space as moral heroes because their dissent confirmed a geopolitical narrative the West already embraced. Publishing them allowed Western institutions to perform solidarity without confronting their own structures of domination. Barghouti’s writing, by contrast, implicates a regime the West funds, arms, and shields diplomatically. This difference is more significant than any biographical parallel with Mandela or Malcolm X.

The Mandela comparison is revealing for what it sanitizes. Western institutions now celebrate Mandela as a universal icon of forgiveness, but once labeled him a terrorist. His radical critique of apartheid and advocacy for armed resistance were softened post-1994 into a narrative of reconciliation. A similar alchemy is now being attempted in advance for Barghouti: isolating the figure from his movement, elevating personal endurance, and downplaying the collective anti-colonial struggle he leads.

This is why Barghouti’s book arrives framed as human rights testimony and prison literature rather than as political theory of settler-colonial rule. The genre frame cushions the blow of implication. Whether this mediation functions as a Trojan horse — allowing readers to politicize the text despite its packaging — or as a neuteringof dissident force remains the central dilemma.

Conclusion: The Metrics of a Stress Test

The “stress test” will have contradictory metrics. Institutional success will be measured by sales figures, prestigious reviews, and literary prizes — signs of absorption into the respectable canon. Political success will be judged by very different indicators: citation in grassroots organizing, use in campaigns for his release, and the virulence of the opposition it provokes. A potent sign of dissident force would be if the book becomes a liability — sponsors withdrawing from events that platform it, furious op-eds from aligned think tanks, organized attempts to remove it from curricula. Backlash is not noise; it is a measure of perceived threat to the narrative status quo.

Even if mediated into testimony, the book’s circulation in politicized publics may still enable readers to extract and amplify its dissident potential, converting moral admiration into pressure for structural change.

Note: First published in Medium.

Rima Najjar is a Palestinian whose father’s side of the family comes from the forcibly depopulated village of Lifta on the western outskirts of Jerusalem and whose mother’s side of the family is from Ijzim, south of Haifa. She is an activist, researcher, and retired professor of English literature, Al-Quds University, occupied West Bank.